American is a Verb

American is a Verb

|

| Creativity Takes Focus |

We the People have pushed forward the evolution of democracy and freedom and - in so doing - of humanity. Now that is threatened by a self-entitled few.

If you have read this column for a while you will probably remember that the late R. Buckminster Fuller (aka “Buckminster” or “Bucky”) was a hero of mine growing up. For that reason alone, it is necessary to give Bucky credit for the title and the conceptual “metaphor” of this column.

There is always a danger inherent in “masquerading” as an etymologist when as sage an individual as Dr. Michael Ferber, who writes the “Speaking of Words” column at InDepthNH.org, actually is.

My columns are always reliably delivered to subscribers of my Substack, but often a column is picked up by The NH Center for Public Interest Journalism, whose news delivery vehicle is its website InDepthNH.org.

I have an exclusive agreement with “InDepth” and I’m proud of that relationship, but like any good publication, they try to make their delivery of news part of a coherent package focused on state and local news and columns. When they choose to run a piece, especially one like this, I hold my breath and tremble to think that one of these days, Dr. Ferber is going to “call me up short” on my lack of expertise and tendency to take liberties, particularly in relation to tangents that I may take as a result of my Native heritage.

|

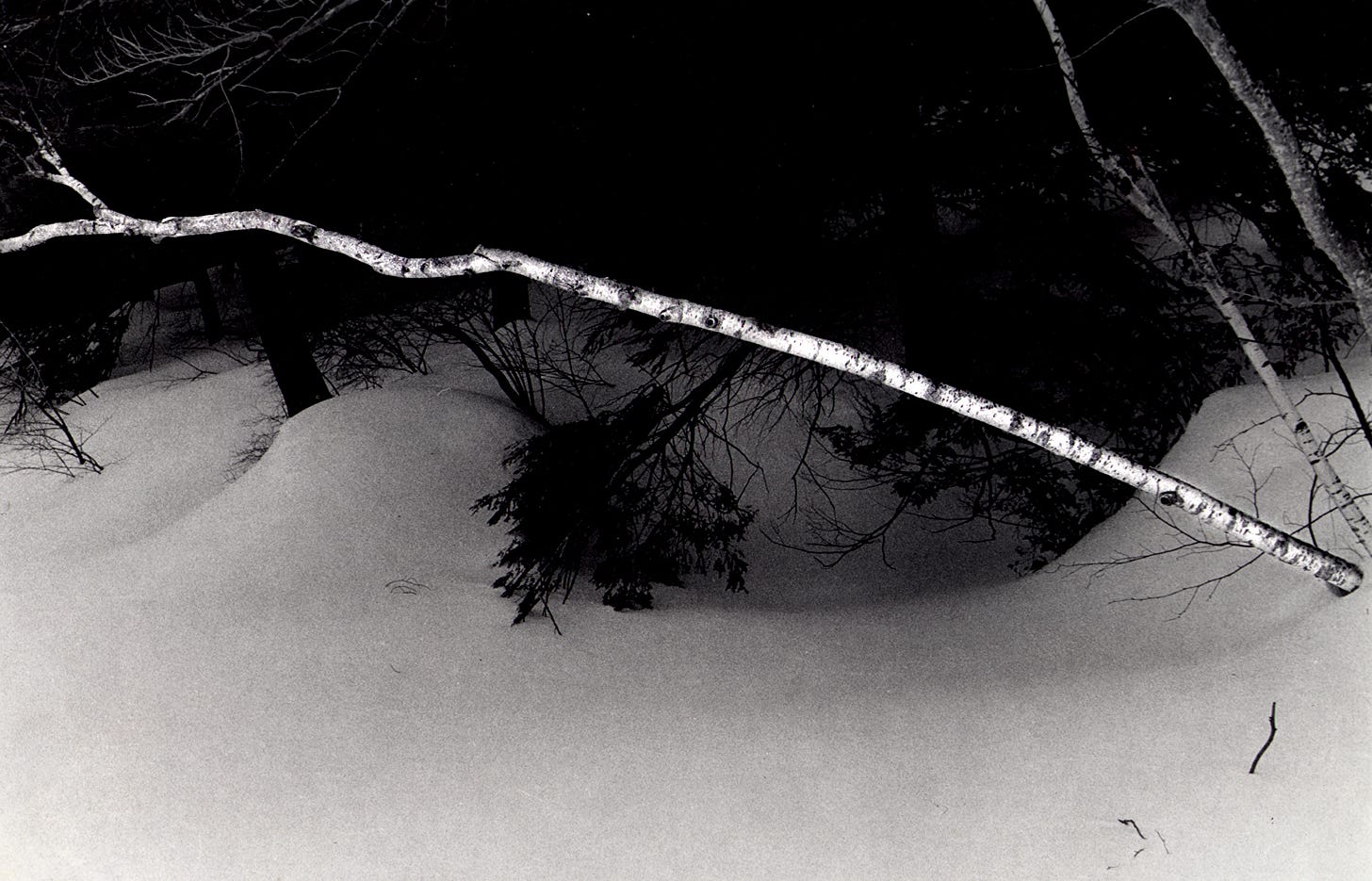

| The Universe in a Minor White Monochrome |

I intend to take such liberties with this column as well, so hold on, and wish me well, as I navigate not only my Native instincts, but also Dr. Ferber’s vast knowledge.

Fuller was an inventor, a prodigious writer, and a crafter of words and phrases. You may have seen references to “Spaceship Earth”, a term invented by Bucky and driven by Fuller’s conviction about the need for all of us to treat our home with the respect necessary to ensure its survival, since our own lives depend upon it.

He was also the inventor of the Geodesic dome, the Diaxion House, and other structures, combining brilliant mathematical understanding and architecture to create structures that - unlike most architecture - are actually stronger as they get larger. Or simply more efficient and cost effective. If we ever establish a colony on Mars, the expectation is that it will be beneath a massive Geodesic dome.

Among the books that Fuller wrote was “I Seem to be a Verb”.

Often his books were tombs worthy of holding a door open in a windstorm; filled with wisdom, mathematical calculations, and thoughts that challenge ordinary intellects like mine.

I Seem to be a Verb was different. It was really chiefly focused on defending the conclusion that he - as it happens, like many of us - could not be characterized, or contained, by a mere noun. That understanding the human condition, especially for Americans, calls on us to see ourselves in a far more passionate, nuanced and engaged way with life and the universe.

Throughout his prodigious body of work, R. Buckminster Fuller consistently references the culture. spirit and actions of Native Americans, and even more broadly, indigenous people across the globe - like the Maori.

To Native Americans, identity is not a static object but an ongoing flow of energy and engagement with the universe. From ecstatic dance like the fabled Sun Dance of the Cheyenne and the Lakota: fasting, singing and dance, lasting for days. To describe ourselves as a verb denotes action, a dynamic state of being,

Fuller, like Native Americans, viewed life and individuals not as static, but part of the ever-changing and fully-engaged cycle of life.

We are not a single object, bounded by the natural world, we are an integral part of the world. One with the cosmos. The “verb” metaphor highlights this emphasis on active participation and utility.

In essence, to be a verb is to celebrate and embrace a different role: an active, integrated function of the universe’s grand, continuous process of transformation. As Carl Sagan often said, “born of Stardust”.

|

| The Red Loft |

To be an American, too, is a verb.

Born of a bold and peripatetic idea. where the bounds of the natural and human-fashioned world are only one strand of an ideal spanning the boundaries between science, art, and philosophy.

Humbly engaged, generation after generation, in the challenge laid out by our founders that with faith in ourselves, we would continue to grow together in community, deeply committed to those dynamic ideals and to the notion that human thriving could be built in a world where freedom and diversity undergirded an order built around rules of law where no man or woman was exempt from its precepts - no man a King, no woman a Queen, except in our own private domains.

Creating order from chaos. Unafraid to confront our own shortcomings, yet determined to always strive to learn from our mistakes and to continue, with a sense of humility, on our journey to “becoming”.

To be all that we knew we could be.

We are not bound by a single religious dogma, but committed to the belief that all those who share our sacred verb are bound to freedom of the mind and body, including the freedom to worship as each sees fit, but beyond that, jealously protective of our individual rights of privacy and bodily autonomy.

Fully aware that an open heart for one another can lead us down a path to truth and happiness, and healthy skepticism can permit us to avoid the pitfalls of that path - vanity and hubris.

As Americans we are not beholden to the boundaries of the Atlantic or the Pacific. We carry our land, and our place in the cosmos wherever we go in our hearts.

We are carved from the souls of farmers, stay-makers, philosophers, soldiers, teachers, frontiersmen, native people, slaves, free-men and free-women, immigrants. Believers in one another and the whole of us.

We are Sons of the Revolution who did not have to wait for their franchise and sons and daughters of the Revolution whose strength of character and patience - tried and forged by centuries of heartache, disapointment and struggle - has been made stronger in the places where we were broken, made wiser in the quiet power born of overcoming.

|

| The Snow Train |

We are the inheritors of Crazy Horse and Chief Joseph, Techumseh and Peacemaker, who’s love of the land and freedom continue to teach us lessons even today.

We are the beneficiaries of Tom Paine, whose words inspired, and George Washington who read those words to soldiers in the freezing cold of Valley Forge.

We are the living legacy of Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery and Abraham Lincoln who was wise enough to carry us through a Civil War to end it.

We walk in the path of Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, Thurgood Marshall and John Lewis who never gave up on the struggle for civil rights and the Adams Family, Abigail, John and John Quincy who from the very start knew we must rid ourselves of the great national shame of slavery.

We are indebted to great minds like Locke, Jefferson, Franklin, Monroe, Thoreau, Richard Goodwin, John Muir and Rachel Carson; The brothers Kennedy, and the cousins Roosevelt, Carl Sagan and Ann Drury, and yes, Bucky Fuller, all of whom have provided us with direction and inspiration to continue to explore the greatness within us and our place in the Cosmos . . .

We are a people of action: every color, every creed, every religion; Our diversity . . . our strength. Our determination . . our super power.

To be an American is to be a verb.

|

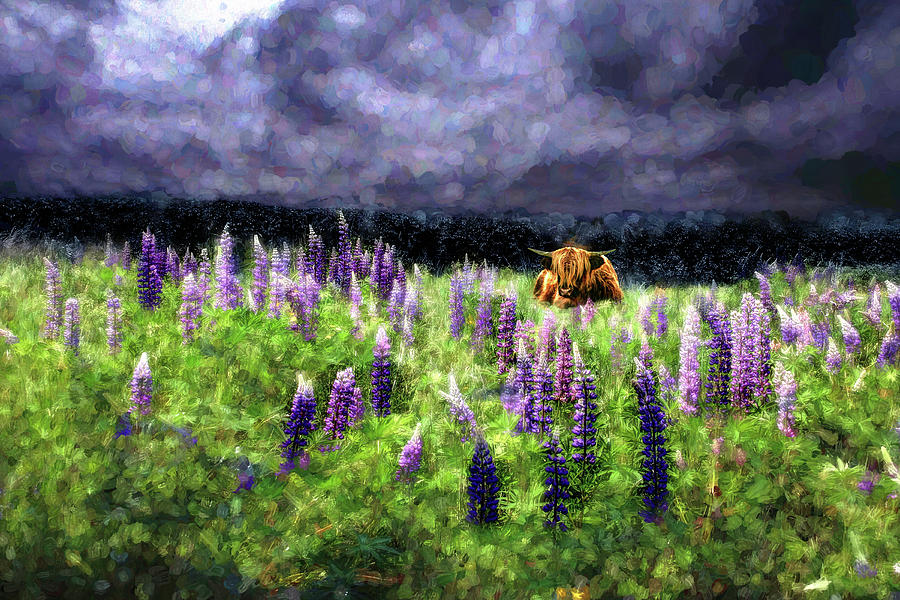

| Rugosa Rose |

Notes and Links:

Some literary references to “Fuller’s” views on Native Americans may refer to his great-aunt, Margaret Fuller, who authored the 1844 book Summer on the Lakes, in 1843, documenting her interactions with the Ottawa and Chippewa tribes.

Margaret Fuller (1810-1850) wasn’t just an aunt; she was a towering figure in American Transcendentalism, a pioneering feminist, journalist, and critic, known for editing The Dial and her seminal work Woman in the Nineteenth Century, with Summer on the Lakes, in 1843 serving as a pivotal text where her evolving views on nature, materialism, and Native Americans (Ottawa & Chippewa) emerged during her Great Lakes journey, showing a shift from pure idealism to social concern.